Hats are not, primarily, fashion items or status markers. They are – overwhelmingly – objects that initially came into use because they fulfilled a concrete function. Whilst they have sometimes acquired status or ceremonial functions as a result of their initial purpose, this is not the way that most styles of hat have come into use, or fallen into disuse.

It surprises me there’s any need to make this argument, given the sheer obviousness of it. But writing about hats seems almost exclusively to assume that they are status items first, and useful items last – if at all. This is, I’d suggest, because the people who write most about hats are those least likely to use them, or even think about them, in relation to situations where they have anything but status or symbolic purposes.

Before I tell you about exactly how those people are wrong, I’d like to address their likely social roles, and how those social roles are likely to predispose them towards arguments based on status.

So, who has to write about the history of hats?

Firstly, companies that make and sell hats. If it’s anything bigger than a small miliners’ shop (the kind of business entirely designed to make status hats) the person doing the writing will be either the owner or a full-time office worker. This writer doesn’t need to wear a hat for work – except possibly to promote the company’s own products. Indeed, this is likely to be a workplace where no-one at all actually needs to wear a hat. All the hat-wearers there will easily accept the claim that hats are symbolic rather than useful.

Even if it causes them to lose sales.

Second, those academically involved in fashion and design, or in the understanding thereof. That is, students of fashion and students of culture. Similarly to those responsible for marketing hats, these are people who work in an environment where there’s no need for a hat.

But their alienation from the functions of hats is more total even than this. Let’s look first at fashion students. They are encouraged to perceive clothes themselves as essentially without function, as solely a form of display. The climactic event in the life of a fashion student (or the designer they seek to become) is the ‘fashion show’. Here the focus is entirely on appearance, and the clothing doesn’t need to last beyond the show itself, or to do anything beyond demonstrating aesthetic sense. There is no reason for anyone in this situation to seek to design for use, or even to attempt to understand why anyone else would.

For those studying culture, and choosing to focus on the hat in particular, there is yet another layer of separation between them and the possibility of hats being essentially functional. This is the dominance, since the late twentieth century, of academic worldviews that see ideas as constituting reality ‘all the way down’ – as being at the heart even of language and sense-perception. Additionally, they are socialised into favouring ‘irony’ and ‘playfulness’ in the discussion of even the most deadly issues, and into a (now somewhat quaint) claim that class has declined in usefulness as a way of understanding culture and politics.

These professional barriers to understanding can result in glaring examples of silliness like the picture and commentary below:

“Contenders for Fashions on the Field at the Melbourne Cup”

“Contenders for Fashions on the Field at the Melbourne Cup”

“Hats once held a high degree of symbolic meaning. They were markers of wealth and class, of a person’s profession or marital status. The class system no longer operates in Australia, and dress codes are more variable than ever before, and so the rules that have governed hat-wearing in the past are no more. As milliners continue to explore non-traditional materials and develop new techniques, women’s hats will continue to evolve, new styles will emerge, and those of us who are passionate about hats will continue to turn heads.”

Torb & Reiner 2017

Here a company making bespoke hats claims that hats are no longer class markers (and that social class no longer exists) – right under a picture of a gaggle of expensively hatted ladies at Melbourne races, standing in front of a sponsorship hoarding for modern status markers Longines and Lexus (Torb and Reiner 2017). To be fair to the company’s writer/s, they may have been leaning on the Wikipedia entry on hats, where a similar claim is made (Wikipedia 1, 2017). Or, if they read more extensively, to the book that the Wikipedia entry uncritically references (Crane 2000).

These barriers to understanding also mean that there has been – until this blog entry – no viable explanation for the surprise return of the hat in the twenty-first century. Platitudes about its return as an individualistic style item or form of self-expression, (“the rules that governed hat wearing in the past are no more”), do nothing more than beg the question – if they’re such a great way of expressing individual identity, why did they decline in popular use in the second half of the Twentieth Century?

We’ll answer that later – and, no, the answer is not ‘because of JFK’. First, now that we’ve understood how it’s possible to fail to understand the functional nature of hats, let’s note some of the myriad purposes we all know that they actually have.

Safety 1 – Collision, Fall and Projectile Protection

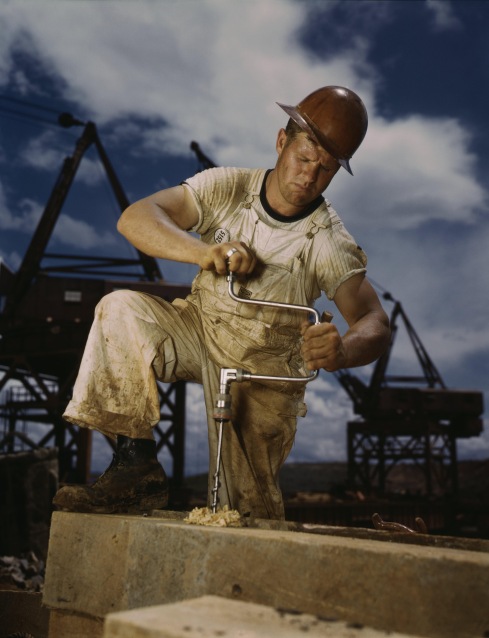

The carpenter pictured at the top of the blog is wearing a hard hat. These, although their design has changed a bit since that picture was taken in 1942 are commonplace or compulsory around building sites, warehouses, steelworks and other identifiably high-risk environments worldwide. They protect the head. They are not particularly comfortable or stylish. They are mass-produced. Where they are worn as a safety requirement, managers, owners, engineers and visiting politicians and monarchs wear them alongside labourers and forklift drivers.

A construction manager wearing a hard hat. (PERI Construction 2017).

A construction manager wearing a hard hat. (PERI Construction 2017).

Similarly, safety considerations lead to protective hats being worn for sports, with surprisingly little personal expression. This cycling helmet, like most sports headgear, is not a fashion choice, but a combination of head protection and crappy advertising hoarding.

Wikimedia 1

Wikimedia 1

Likewise, the defining item of military headgear is not much about status or rank, but about head protection and showing which side you’re on:

wikimedia 2. These young men don’t appear to be primarily motivated by self-expression in their hat and hat accessories.

wikimedia 2. These young men don’t appear to be primarily motivated by self-expression in their hat and hat accessories.

Temperature and Light Correction

Hats of almost limitless variety function keep our head, neck, face, eyes and ears warm, cool or free from sunburn, sunlight or darkness. Some we don’t even usually think of as hats.

Wikimedia 3 Inuit child’s outfit (with built-in hat)

Wikimedia 4 – A sun hat

Wikimedia 4 – A sun hat

wikimedia 5. Another sun hat

wikimedia 5. Another sun hat

Wikimedia 6: A beanie, modelled by a St. Petersburg street sleeper. We’ll be revisiting this hat.

Wikimedia 6: A beanie, modelled by a St. Petersburg street sleeper. We’ll be revisiting this hat.

Temperature or light control is the prime reason most of us wear hats. It’s also key to understanding the decline of the hat in the later Twentieth Century; and its resurgence – with a radically changed meaning – in the Twenty-First. And whilst this is not really about JFK, disposing of the myth that he singlehandedly killed the hat is part of the journey.

From Capone, to Kennedy, to the Millenium

i. The Gangster

The tenth episode of Boardwalk Empire, ‘The Emerald City’, can be understood as essentially a set of filmic meditations and jokes about hats and hatlessness during Prohibition. Sadly, we’re only exploring one of its stories here.

Al Capone, early in his rise to power, is portrayed as a tough, young, cloth-cap wearing joker. Such a joker, in fact, that he jeopardises his chance of making it big in the underworld by giving his boss, Johnny Torrio, a joke cigarette in a packed room during a meeting. His boss (like the cigarette) explodes. Although Capone later accompanies Torrio to a colleagues’ sons’ barmitzvah, he’s clearly out of favour. Instead of being introduced around, he’s sent off to go and find a seat.

He gets chatting to the guy in the row ahead of him, who tells him that in a synagogue, unlike in a church, he’s expected to keep his hat on. But then, more importantly for the plot, he tells him that he should get a Yarmukah – the cap he is wearing is suited only to a boy, someone who has yet to begin ‘unlearning the follies of … youth’. Capone takes the point, although he puts it into practice by getting a fedora. He’s wearing this when we next see him in the lobby of Torrio’s club – although he quickly removes it as a mark of (religious?) respect. What follows is his Henry IV moment, as he promises Torrio to take his work seriously from now on, and – despite Torrio’s suspicions – manages to get the step up he’d been waiting for.

Let’s unpack the some of the meanings of all those hats, and see how they relate to function. In the exploding cigarette scene neither Torrio nor Capone is wearing a lid. There are some men around who are, but only men who are wearing cloth caps – practical wear that can be put on or taken off quickly and easily, does not have to be held carefully, will keep you warm outside in a cold Chicago night but can fit in a pocket when you hit a bar or a cathouse.

In the synagogue scene both men wear their respective hats – Torrio the trilby, Capone the jokey cloth cap. There’s a better explanation for the difference between church and synagogue etiquette on hats than is given by the gentleman in the yarmukah, however. This is that the difference in etiquette simply reflects the climate of the religions’ prime centres of power in their formative period.

Thus for Judaism, formed in hotter climes, temperatures inside are likely to be lower than those outside. As a general rule, a hat will be a reasonable corrective. For most incarnations of Christianity, however, the outdoor climate of their home region has been colder and wetter. Most competently made buildings would be warmer inside than out once a congregation appeared, and outdoor hats left on would become increasingly uncomfortable, and smelly, over the course of a long service.

When Capone and his fedora visit Torrio, the newly mature young gangster is signalling that he is now someone who can afford the cloakroom, and always will be. He has left forever his membership of that juvenile age that doesn’t look after its clothes – and of that class of men who need to save on the hatcheck bill. Nobody is going to mistake him for a deliveryboy again.

But, note well, that status shift originates in the design and material nature of the hats in question.

Boardwalk Empire‘s Capone is of course a creature of fiction. But this is fiction that is in business because of attention to historical detail, and it can therefore teach us a great deal. John F. Kennedy, on the other hand, is a historical figure in business because of selective recollection and reasoning so gross it resembles fiction. Here, our first task is to address a lie.

ii. The Myth of Hatless Jack

“The fedora has never made a comeback. The big hat-makers never forgave John F. Kennedy for appearing at his inauguration bare-headed, thus permanently ruining their business by making hatless a popular style for men”.

(quoted and disproved – but, sadly, not fully referenced – in an otherwise excellent article in Snopes, from where the Washington Post picture below also derives).

The claim that John F. Kennedy didn’t wear a hat to his 1961 inauguration, as we can see from the Washington Post photo above, is simply not true (Snopes). It was well below freezing that day, and if he hadn’t worn a warm hat for some of it his presidential term could have been even briefer. But it would indeed be true to say that he rarely wore hats later on.

Like millions of other Americans, he didn’t need to.

This was not, contrary to myth, fashion historians and hatmakers (Crane 2000, Torb & Reiner), because of the sudden demise of the class system. The class system never went away. Nor was it because of the elaborate system of etiquette that is often claimed to have characterised hatwearing (ibid). Nor was it because a youthful new age wanted to show off its hair – 1961 was a universe away from the Summer of Love, and the brief explosion of youth culture that had been associated with Elvis looked pretty dead until the ‘British Invasion’.

It was because of air-conditioning and heating.

Between Eisenhower’s election in 1953 and Kennedy’s in 1960, air-conditioning systems had become normal for American homes and offices. As it already was in theatres and cinemas (Steinmetz 2010). Americans no longer needed to correct their body temperature with a hat when they went outside – they just got back inside.

‘Inside’, for around twenty per cent of Americans, could be a car with fully controllable air-conditioning and heating – available since 1954 (Wikipedia 2). For many more, inside could be one of the new enclosed shopping malls that appeared in the same decade in America, Canada and Sweden (Wikipedia 3). For John and Jackie Kennedy, it could also be the newly delivered Air Force One, the first purpose-built presidential jet – with all the comforts of an air-conditioned presidential home and office (Door 2016). Or its sister helicopter Marine One (ibid).

For the Kennedys, as for a fast expanding fraction of the world, there was no outside temperature left to control.

The hat, it seemed to everyone, was obsolete. Even though, as far as I can see, I’m the first person to have understood why.

iii. The Return of the Hat

But Kennedy’s decade was also the last decade before scientists understood that the world was getting warmer and wetter and more meteorologically unstable, because of human action. It was also the last decade of the brief interval of relative human equality that opened with the Russian and German revolutions of 1917 and 1918 and ended with the stagflation of the OPEC Oil crisis from 1973 and the rebirth of ‘free market’ economics in Jim Callahan’s 1974 speech to the British Labour Party conference.

Since the 1970s the material conditions have been spreading for a return of the hat.

Without state-led redistribution wealth accrues to the owners of wealth in capitalist society (Piketty 2014). And the effort to force states to redistribute – even if it happens – won’t be simple or straightforward.

Meantime, whilst inequality and insecurity rise, so will hat wearing.

In America, the global home of air conditioning, the malls – at least the ones where the working-class shopped – are dying (Schwarz 2015). They are being replaced with – nothing. On the streets and the corners, all through the jaded, brave and faded new outside world, beanie hats and baseball caps are worn against the cold and the heat. In Russia and its continental empire, the shock therapy that followed the fall of the Soviet Union has dramatically increased homelessness, and the same hats – as we saw above – are worn there. Across dark Mediterranean nights refugees seeking shelter in the hard heart of fortress Europe cover their heads against the cold. In Britain benefit claimants die of cold and of the terror of debt, bailiffs and heating bills.

As I walked out of my local public library after my first afternoon of research for this blog, I looked up and down the street. I pushed my trilby down tighter against the wind. Everyone around me – or at least the pedestrians – were wearing beanies, or hoodies or both. The car drivers going past, every one, was hatless.

So here’s my fashion prediction for the 2020s and beyond: the hat, worn initially for strictly functional purposes deriving from climate instability and economic misery, will return to being socially dominant. Fashionistas and cultural commentators will fail to notice, because homeless people and refugees are not striding down the catwalks modelling heatgel beanies. The privileged will be hatless, or will wear hats jokingly, for a while longer.

Until the day they walk out of their front door and realise that their bare head feels just like a target.

References

The opening image is: Alfred T. Palmer, TVA carpenter (1942), and is referenced in the appropriate spot below.

Crane, Diana (2000) Fashion and Its Social Agendas: Class, Gender and Identity in Clothing, University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Door, Robert F. ‘Air Force One: A History of Presidential Air Travel’ 10-11-2016 https://www.defensemedianetwork.com/stories/air-force-one-a-history-of-presidential-air-travel/ Accessed 14-11-2017

Palmer, Alfred T. (1942) TVA Carpenter – Library of Congress Print / Photo ID fsac.1a35241.https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Alfred_T._Palmer#/media/File:Carpenter _at_the_TVA%27s_Douglas_dam_on_the_French_Broad_River,_Tenn.jpg/ Accessed 17-11-2017

Konner, Lawrence (2010) ‘The Emerald City’. Episode 10, Series 1 of the HBO production Boardwalk Empire. Episode directed by Simon Cellan-Jones.

PERI Construction (2017) https://www.peri.co.za/projects/industrial-structures/northwest-redwater-project.html Accessed 10-11-2017

Piketty, Thomas (2014) Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Harvard University Press, London

Schwarz, Nelson D. ‘The Economics (and Nostalgia) of Dead Malls’ New York Times 3rd Jan 2015, via https://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/04/business/the-economics-and-nostalgia-of-dead-malls.html Accessed 15-1-2017.

[Additional note… Schwarz claims that the ‘death of the mall’ idea overly simplistic and the real picture is more ‘nuanced’. But his case is that high end malls are thriving, whilst the others – where the ‘middle class and working-class’ used to shop – are closing. In an era when the rate of economic divergence is increasing, that adds up to bad news all round for the mall.]

Snopes https://www.snopes.com/history/american/jfkhat.asp Accessed 14-11-2017

Steinmetz, Katy ‘Air Conditioning’ Time Magazine 12th July 2010, via http://content.time.com/time/nation/article/0,8599,2003081,00.html Accessed 14-11-2017

Torb and Reiner: http://www.torbandreiner.com/MillineryMaterials/history-of-millinery accessed 10/11/2017

Wikipedia “Hat” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hat accessed 10/11/2017

Wikipedia “Automobile Air Conditioning” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Automobile_air_conditioning#Nash_integrated_system

Wikimedia 1 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Giro_helmets#/media/File:Bike_helmet_with_Google_logo_1.jpg Accessed 12/11/2017

Wikimedia 2 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_British_Army_in_Normandy_1944_B6918.jpg Accessed 12/11/2017

Wikimedia 3 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:T%C3%B8j_til_barn_fra_Netsilikinuit_i_arktisk_Canada__Child%E2%80%99s_clothing_from_Netsilik_Inuit_in_Arctic_Canada_(15330292175).jpg Accessed 12/11/2017

Wikimedia 4 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Woman_in_sunhat,_Bondi_Beach_(31668995355).jpg#/media/File:Woman_in_sun-hat,_Bondi_Beach_(31668995355)_(cropped).jpg Accessed 12/11/2017

Wikimedia 5 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Visors#/media/File:Vyacheslav_Pimenov_1.jpg Accessed 12/11/2017

Wikimedia 6 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Homeless_people_of_Russia#/media/File:%D0%91%D0%BE%D0%BC%D0%B6_%D0%B2_%D0%BC%D0%B5%D1%82%D1%80%D0%BE.jpg Accessed 12/11/2017

Leave a comment